Anatomy and art have always been closely linked. Doctors and artists share their common interest for the human body. Prior to the invention of photography artist recorded the knowledge discovered by dissection. The representation of anatomical knowledge was often influenced by artistic styles of the time.

It took centuries for academic dissection to be established and for accurate anatomical knowledge to be gained, recorded and taught.

It is presumed that the Ancient Egyptian had anatomical knowledge resulting from their burial practices, but no records survived. Dissection was first recorded in China 1000BC and there is evidence that in ancient Greece animals were used for dissection. In 300 BC first steps towards factual anatomy were taken in Egypt, Ptolemaic School of Medicine, however terrible accusations regarding practices used at the school, discredited their research. In Europe Claudius Galen (129-201) was the first serious researcher, a medical officer working with Gladiators in the Roman Empire (Simblet 2001: 10). His knowledge and techniques ruled anatomical research till the Renaissance.

In Italy the first book about anatomy was published in 1491 Dissection for teaching anatomy based on research by Mondino de’Luzzi and in Padua, in 1594 the first anatomical theatre was built and anatomic research was given an academic framework linked to medicine as well as a place where dissection could be performed. The anatomical theatre was built like a theatre with seating surrounding a centre stage. Dissection was a seasonal business, as bodies would decompose too fast in the summer and it was only possible during the cold winter month. In the sixteenth century anatomical dissection became very popular and drew large groups of spectators. Other influential schools were founded by the end of the 16th century in Bologna and Leiden, these schools laid the foundation for modern anatomical knowledge and research.

Leonardo Da Vinci’s (1452-1519) work and “knowledge was considerably in advance of contemporary science” (Simblet 2001: 12) of his time, well known today, but Da Vinci’s work was first published 300 years after his death, when it had great influence on the 19th and 20th century depiction of anatomical information.

From an illustration point of view the most interesting examples of historical anatomic research and its representation are the following two books:

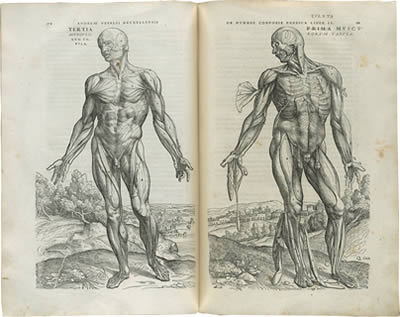

De humani corporis fabrica (on the fabric of the human body) by Andreas Vesalius published in 1543, University of Padua (Fig. 2). “De Fabrica’s ‘muscle men’ are the most famous medical illustrations in the history of the printed book. They illustrate the musculature of the body through a series of progressive dissections. The bodies are posed in front of what appears to be the countryside around Padua: the first six frontal views and six back views can be placed together to form a continuous landscape. In the accompanying text, Vesalius expresses the hope that the figures will prove useful as models for ‘the painter, the sculptor, and the moulder’, as well as for physicians.” (British Library Online, 2014)

The University of Leiden published in 1747 Tabulae Sceleti et Musculorum Corporis Humani a work by artist Jan Wandelaar and anatomist Bernard Siegfried Albinus. Here the dissected body is placed “with exotic animals, botanical specimens, classical ruins and the occasional cherub flying amid billowing silk.” (Simblet 2001: 19)

Today the topic of anatomy still interests many artists. While researching the topic body in illustrations, I came across the paintings of Fernando Vicente (born 1963) an Spanish painter and illustrator. He’s painting series Vanitas (Fig.1) combines paintings of beautiful women with anatomical drawings with amazing results (his website is also worth visiting http://www.fernandovicente.es). Images by Danny Quirk Anatomical Self-Dissection are quite similar but equally fascinating.

Sources:

Lee, C. ‘Observing the body’, Irish Arts Review, Autumn (September-November 2010), pp. 102-105

Simblet, S. (2001), Anatomy for the artist. London: Dorling Kindersley

Vincente, F. www. fernandovicente.es

British Library Online. [online] Available at: http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/ttp/vesalius/accessible/pages15and16.html [Acessed 9 December 2014]

Picture:

Fig. 1: Fernando Vicente, http://cdn.artboom.info/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/Fernando-Vicente.jpg [Accessed 21 November 2014]

Fig. 2: Andreas Vesalius (1543) [online] Available at: http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/ttp/vesalius/accessible/images/pages15and16.jpg [Accessed 9 December 2014]

Fig. 3: Tabulae Sceleti et Musculorum Corporis Humani, Tablae 4 (1747) [online] Available at: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/historicalanatomies/Images/1200_pixels/Albinus_t04.jpg [Accessed 9 December 2014]